Past seminars

Subscribe to the SHU Recreational Mathematics Research Cluster mailing list to access recordings of past talks. Once you are subscribed, you can access past messages to the list including links to recordings. Talks are recorded for members of the cluster only, so are not posted publicly, but there is no cost to join the mailing list.

4-4.45pm BST

How many chess rooks or queens does it take to guard all squares of a given polyomino? This question is a version of the art gallery problem in which the guards can ‘’see’’ whichever squares the rook or queen attacks. We show that n/2 rooks or n/3 queens are sufficient and sometimes necessary to guard a polyomino with n tiles. We then prove that finding the minimum number of rooks or queens needed to guard a polyomino is NP-hard. These results also apply to d-dimensional rooks and queens on d-dimensional polycubes. Finally, we use bipartite matching theorems to describe sets of non-attacking rooks on polyominoes (this is joint work with Hannah Alpert).

Erika Roldán is currently a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellow in the EuroTechPostdoc Programme at the Technische Universität München (TUM) and EPFL Lausanne. Her research interests include biomathematics, stochastic topology, topological and geometric data analysis, extremal topological combinatorics, discrete configuration spaces, recreational mathematics, learning analytics, and educational technology.

9.30-10.15am GMT

When I was at school some of my teachers (in both maths and physics) used to set us exercises where we were shown arguments which were not necessarily correct and had to identify problems in them. This is how I first encountered the flawed Martingale gambling strategy. I will talk about another gambling myth with some international spread that seems less well known, partly as an excuse to talk about Markov Chains. Maths can be useful to defend oneself from charlatans!

Adam runs games and puzzles tables at open days: He used to be known as Pisa University Fraud Department but in recent years L’Omino dei Giochi (Little Games Guy) is what people have been calling him and he can live with that.

9.30-10.15am GMT

The purpose of this presentation is to share with you my enthusiasm for chess problems. First, I will justify the claim that chess problems are mathematical. Then I will give an overview of the world of chess problems. Note that in discussing chess problems, no knowledge of chess strategy is required. Indeed, it can be a hinderance! Only knowledge of how the pieces move is required.

4.00-4.45pm GMT

Dr Sabetta Matsumoto from Georgia Institute of Technology will be discussing creative crafts and math research. What can physics learn from crochet? How does a simple stitch change the stretch of a scarf, and how are modern materials and manufacturing learning from their wooly ancestors? Join Dr Matsumoto for a talk about curvature using pattern making, symmetries using quilt squares and flags, hyperbolic space using quilting at crochet, and knot theory and coding using knits.

Dr Sabetta Matsumoto is an Assistant Professor in the School of Physics at the Georgia Institute of Technology. She is passionate about using textiles, 3D printing, and virtual reality to teach geometry and topology to the public.

4.30-5.15pm British Summer Time

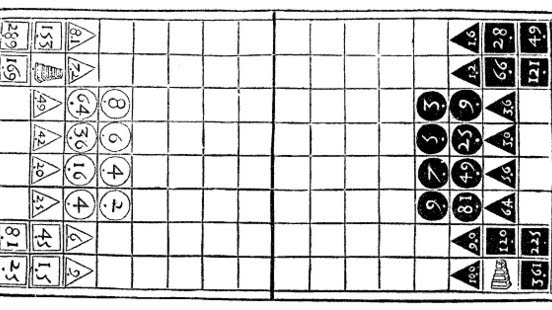

In the Middle Ages, the study of Boethius’ De Arithmetica was the core of the curriculum at Medieval University. The Quadrivium was divided into Arithmetic, Geometry, Music, and Astronomy. Rithmomachia was a strategy math board game, originally designed by von Würzburg (circa 1077). Some of the most notable manuals were further developed by De Boissière, Lever and Fulke, and Varchi, Strozzi, and Barozzi in the early Renaissance. After the Enlightenment, with the curriculum change, the game lost its popularity and gradually disappeared. The works of Smith and Eaton, and more recently of Moyer brought back the game to the academic study. We have found evidence of modern Number Theory in the number pattern of Rithmomachia and its cousin Metromachia, we will describe how some of the foundations of the game lead us to Fibonacci, Pell, and Jacobsthal numbers. We will present the most current results achieved by the Rithmomachia Research Center at Gonzaga University.

10.00-10.45am British Summer Time

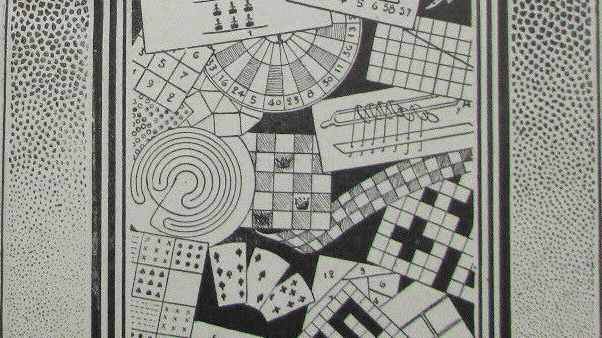

In 1935 and in 1937 the Congrès International de Récréation Mathématique took place respectively in Brussels and France. Paired with the World Fairs which happened in these cities, this meeting brought together multiple ingenious minds who exchanged on various tópics ranging from number theory to the annals of (combinatorial) game theory. This presentation on ongoing research done jointly with Lisa Rougetet, will address the event, it’s participants and organization, as well as, highlight some of its content like cryptarithms, chessboard problems, and other puzzles.

Many popular recreational maths puzzles involve logic - liars and truth-tellers, known and unknown facts and deduction from given statements. However, these types of puzzles can offer opportunities for ambiguity, especially given the precise nature of mathematical thinking and the frustratingly inexact English language. I’ve collected some examples of such puzzles and the traps you can fall into while writing them, and offer some general advice to improve wording and close any logical loopholes.

Mathematical puzzles have been a source of fascination to many over the centuries. But what is the point of a puzzle? Is it just about an elegant piece of mathematics, or to find out what would happen in a real-world situation, or is it really about something else entirely? Does the enjoyment come from solving, or from understanding the solution? This informal talk will look at examples, simple and difficult, abstract or “real-world”, going back to the first printed mathematics book in English (1536) and up to puzzles presented to the public during lockdown in 2020.

Imagine four friends are about to start a game and need to decide the order of play. The friends decide to roll dice and order play from highest to lowest. Is it possible to make a set of dice so that no ties occur, and each player has an equal chance of being first, second, third and fourth? In 2012 Robert Ford and Eric Harshbarger solved the problem with a set of four 12-sided dice. However, the problem for five players remained open. We present two solutions for five players with different interesting features, how these methods can be applied to more than five players, and finally some questions still be answered.

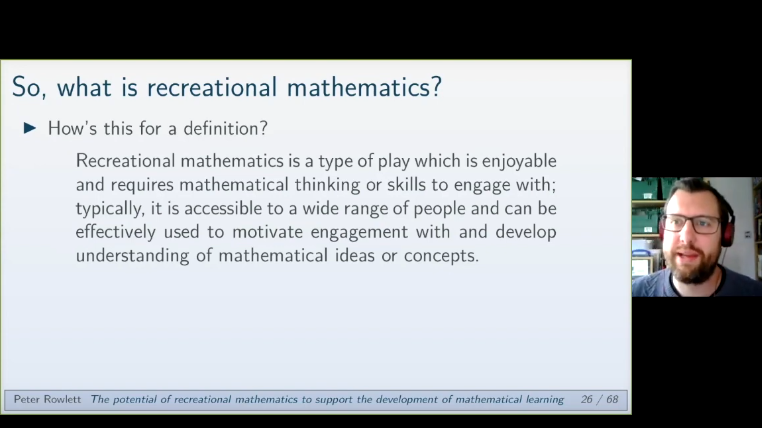

A literature review establishes a working definition of recreational mathematics: a type of play which is enjoyable and requires mathematical thinking or skills to engage with. Typically, it is accessible to a wide range of people and can be effectively used to motivate engagement with and develop understanding of mathematical ideas or concepts. Recreational mathematics can be used in education for engagement and to develop mathematical skills, to maintain interest during procedural practice and to challenge and stretch students. It can also make cross-curricular links, including to history of mathematics. In undergraduate study, it can be used for engagement within standard curricula and for extra-curricular interest. Beyond this, there are opportunities to develop important graduate-level skills in problem-solving and communication. The development of a module ‘Game Theory and Recreational Mathematics’ is discussed. This provides an opportunity for fun and play, while developing graduate skills. It teaches some combinatorics, graph theory, game theory and algorithms/complexity, as well as scaffolding a Pólya-style problem-solving process. Assessment of problem-solving as a process via examination is outlined. Student feedback gives some indication that students appreciate the aims of the module, benefit from the explicit focus on problem-solving and understand the active nature of the learning.